This is literally the multi-billion-dollar question when it comes to Pennsylvania’s hardwood forests (Pennsylvania is the number one exporting state for hardwoods), grape industry (number 5 nationally), apples (number 3 nationally) and landscapes regarding spotted lanternflies. This is what we call a “hot tree”, and we can use this fact to our advantage killing spotted lanternflies. Often on a given property, amongst trees of the same species, there will be preferred specimens, meaning that of three silver maples one is absolutely covered with spotted lanternflies, and the remaining two are not. This means that they will choose certain species first if possible but settle for what is available. That said, they tend to have preferred choices that they feed on, such as Ailanthus, walnuts, or grape vines. Spotted lanternflies are known to “host” (feed) on many different hard wood trees that we have in our landscape. On a hot, breezy day they can be seen crashing into houses, cars, trees, or anything else that they encounter.

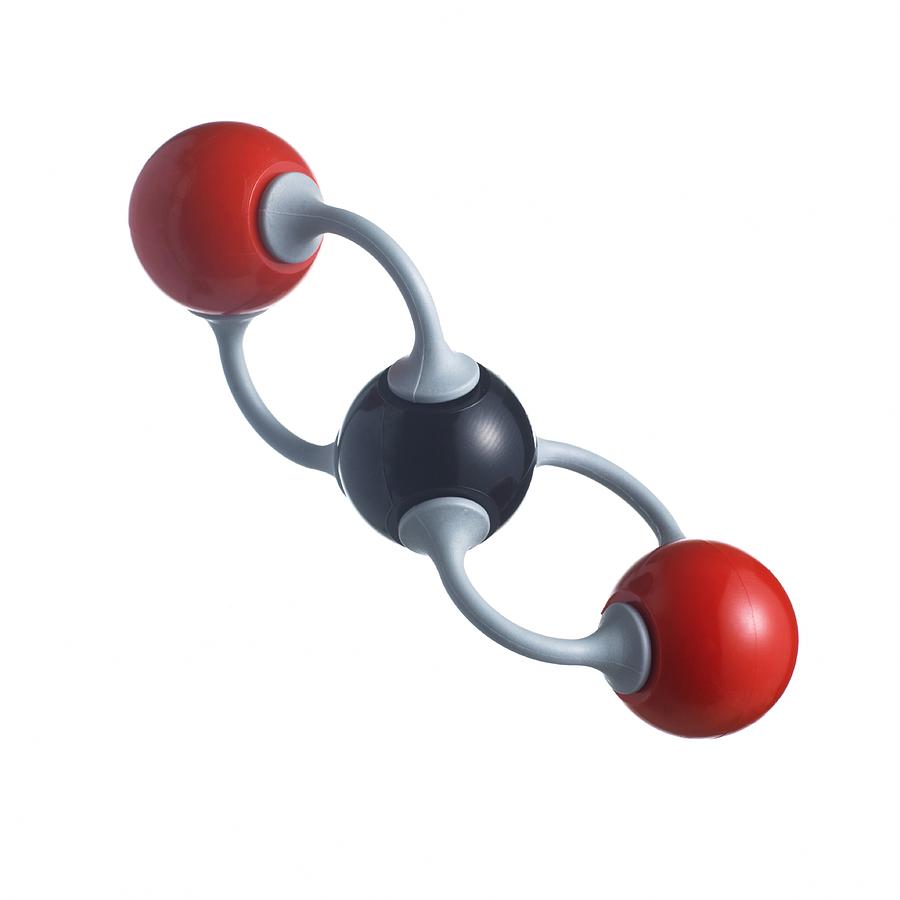

They can fly relatively high and far, but not with any great level of agility. While they are powerful hoppers (hence the term planthopper), additional observations have changed this notion. Early on, people first encountering them reported them as “not able to fly far, but short distances similar to a grasshopper”. They are not agile like a dragonfly or housefly, but more like a moth. Once at the top of the poles, they spread their wings and take advantage of the height to fly further distances. We have even observed them climbing telephone poles in areas without tall trees. They also like to gather on warm house surfaces when the weather is cool. They have no interest in your house, it’s just in their way. Spotted lanternflies take advantage of any structure to rest or climb on. They likely utilize small existing holes in tree stems and trunks that are so small, they are nearly microscopic. Spotted lanternflies do not have chewing or biting mouth parts. The proboscis is located between the two front legs. Spotted lanternflies feed by sucking sap from plants with a straw-like mouth part called a proboscis.

They have a very wide range of host plants. They prefer Ailanthus trees (tree of heaven), walnuts and grape vines as a first choice, most any other hardwood tree as a second choice and with much less frequency, pine trees. Spotted lanternflies eat sap from plants. Each egg mass usually contains 30-50 eggs, and we believe a female can lay 2-3 egg masses before they die. Undisturbed egg masses will overwinter and then hatch out in the spring, continuing the cycle. The adults will continue to feed intermittently after egg laying and hang around until a heavy frost kills them. The eggs are laid in groups and the groups are contained in a plaster-like covering in masses. Around the third week in September, they begin mating, and then they lay eggs. The adults then begin to migrate out to new areas (especially on warm, breezy days) from the end of July through October. The final molt into adults begins somewhere around the third week of July, but individuals can remain in the late nymph stage as late as October. In the fourth stage, the nymphs are more conspicuous as they are larger and red in coloration. In the first three stages, nymphs are black with white spots and can be easy to overlook, as they are small and look somewhat like ants. The nymphs hop around and feed, molting several times before their final molt into adults that can fly. They hatch in the spring as wingless nymphs. There can be secondary damage in the form of sooty mold, egg mass residue and similar issues. No, not directly in the manner that termites or carpenter ants can do structural damage. (Check out the picture of the tarsal claw in our photo section) Can they damage my house? The only thing close to a bite we have experienced is a pinch or poke from the legs of the lanternflies hanging on to us. We have personally been in highly infested areas and literally covered with dozens of spotted lanternflies at a time and have never been bitten. We have heard several stories of and from people who think they have been bitten by a spotted lanternfly but couldn’t swear that they either saw the physical bite take place, or that it wasn’t a horsefly, mosquito, or other such native insect. Their mouthparts, which are fused into a straw-like beak that they insert into plant tissue to suck up sap (phloem), are not capable of penetrating human skin. Spotted lanternflies, however, are native to countries in South East Asia. We have many native species of planthoppers in the US. Spotted lanternflies (Lycorma delicatula) are planthoppers from the order Hemiptera like our native aphids, cicadas, or leafhoppers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)